Paul Alker, Liam Miles and Emma Armstrong

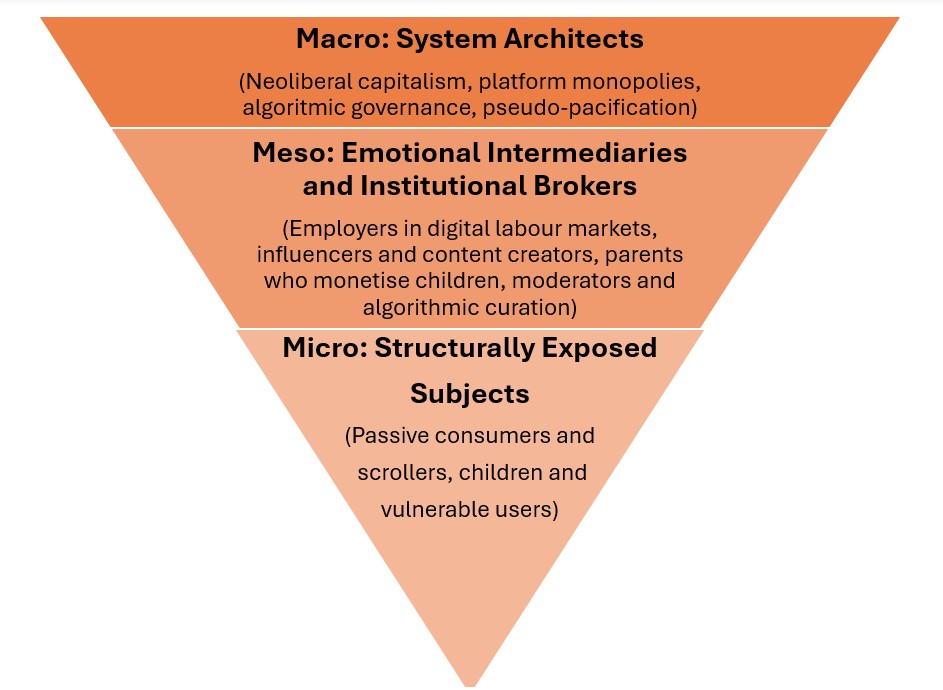

As outlined in the first post of this series, the overarching aim of these theoretical interventions is to shed light on the key determinants of the rising levels of violence against women and girls (VAWG) in its myriad forms. It is our belief that a multi-level critical analysis of the issue is essential if we wish to fully comprehend the various causes of this violence on a symbolic and subjective level – violence that women and girls are experiencing with greater frequency and severity. In this post, as a precursor to further investigations of the meso and micro levels, we will focus on some of the main macro-level factors, which are the large-scale social systems and structures that contextualise the cultural forms involved in this violence.

As Lynes et al. (2021) illustrate, adopting an initial macro approach to understanding violence enables us to explore the issue of VAWG from a novel and often overlooked vantage point, affording us the opportunity to emphasise the broader social forces that create the conditions in which such violence takes place. From this position, a key debate in contemporary discussions of VAWG concerns the role of patriarchal power in late-capitalist societies. Some question whether patriarchy remains as dominant and influential as it once was or whether it has been displaced by other power structures (Lynes et al., 2021). Yet, Yardley (2020) argues that patriarchy does indeed still exist but it has undergone a mutation under neoliberalism to become what she terms ‘neoliberal patriarchy’.

This iteration of patriarchal power operates through the celebrated neoliberal principles of hyper-individualism, instant gratification, hostile competitiveness, hedonism, narcissism, and success premised upon the failure of others. These zero-sum values are clear in the behaviour of many who perpetrate violence and harm against women and girls. Exhibiting a sense of what Hall (2012) calls special liberty, in which sovereign individuals follow the libertine drive to satisfy their own self-interest, regardless of the harm it may cause to others, for both expressive and instrumental purposes (Kotzé, 2024). This is a concept we will explore further in a forthcoming post on micro-level factors.

Alongside the neoliberal shift towards competitive individualism, identity-based divisions, such as race and gender, have increasingly replaced class as the fundamental structures of inequality (Žižek, 2002). In the absence of the traditional class struggle, this shift has fostered ‘culture wars’ in which men and women are positioned as adversaries, with identity politics weaponised to fuel antagonism rather than solidarity. Hall and Winlow (2014) refer to this as the construction of a ‘society of enemies’, in which both individuals and various identitarian groups are encouraged to view one another as pseudo-pacified competitors rather than allies. In the context of a society of enemies, the concept of neoliberal patriarchy enables us to appreciate the ways in which misogyny is effectively sewn into the fabric of late-stage capitalism (Yardley and Richards, 2023). Rather than being a deviation from contemporary social values, perpetrators of VAWG can be seen as extreme embodiments of the neoliberal ethos. In the forthcoming micro-level post, we argue this leads some men to believe that women are responsible for ‘stealing’ something that is rightly theirs, resulting in violence that manifests in both symbolic and subjective forms.

The intersection of politics, economics and violence in relation to VAWG is indeed a global phenomenon. A striking example of this is found in Mexico, where Rodriguez’s (2012) research explores the manner in which the anarchic confluence of global capitalism, alongside Mexico’s corrupt national politics, has displaced transient populations of people seeking work. Narco-warfare has enabled the emergence of The Femicide Machine: an apparatus that did not only create the conditions in which dozens of women and young girls could be murdered, but also developed the institutions that would guarantee impunity for those who perpetrated such crimes. Žižek (2016) frames this as a form of macho reaction to an emerging class of independent working women. Sayek Valencia (2019) further highlights the prevalence of this issue by presenting the staggering statistic that, at the time of writing, every four hours in Mexico a young girl or adult woman is killed.

There are two common threads present across these authors’ assessments of the violence being perpetrated against women and girls. One, that it is extremely brutal in nature, and two, that it is inextricably linked to the social, cultural, political and economic context in which it takes place. Valencia (2018) argues elsewhere that this culture of extreme violence in Mexico would not exist were it not for the economic crisis the country suffered in the 1980s; the breakdown of the nation-state which led to an unholy alliance between politicians and the cartels, and the catastrophic shortcoming of NAFTA in the 1990s.

There are of course a number of contextual differences between the causes of violence against women and young girls being perpetrated in Mexico and the UK. Yet, we should not understate the role of the social and economic changes within the UK over the past four decades alongside some of the positive cultural changes that have occurred in the realm of women’s rights. What the examples of VAWG in Mexico illustrate is the importance of considering the macro context in which violence is taking place and the subsequent need for significant interventions at the macro socio-political and cultural levels.

Turning to the UK context, the Cost-of-Living Crisis (COLC) as a mediated and political term, can be utilised as a timely example of how risks in late-modern society permeate the fabric of everyday life and its social practices to produce and heighten the experience of ontological insecurity (Giddens, 1991). These insecurities can be traced through the rise of food poverty (Francis-Devine et al., 2024), the housing crisis, in which many, particularly young people, struggle to access affordable housing (Atkinson and Jacobs, 2020) and insecurity in the labour markets, following a flexible and increasingly precarious turn (Lloyd, 2018). It can be argued that through neoliberal politics, the social emphasis on raising aspirations through centring the individual’s life journey, or what Beck (1992) denoted as reflexive modernisation, has been exposed as a lie, as in the contemporary moment, the opportunities to attain symbols of success are few and far between. Moreover, as Sanz (2017) suggests, the socialisation practices for men and women have seldom changed and largely retained the binary dichotomy of gender.

According to Ellis (2015), for many men living in post-industrial Britain, the norms around displaying masculinity remain. The male body has lost much of its value in the labour force. The attributes of physical strength and toughness have become redundant, replaced by a greater emphasis on cognitive abilities and communication skills, but a vestigial visceral habitus continues to be reproduced in some locales (Hall, 1997; Hall et al., 2005). This has created a situation in which many men are faced with the terrifying abyss of their own insignificance, in the absence of opportunities to gain any positive form of recognition from others (Ellis, 2015; Gibbs et al., 2022).

As they struggle to accept this situation, articulate their growing frustrations and channel their libidinal energies in a positive or productive direction, a cacophony of negative emotions are allowed to develop – feelings of anger, shame, envy – the end result of which is often either implosion or explosion. Alcohol and substance misuse, depression and suicide characterise the former, whilst street-level and domestic violence against partners and children become the explosive chosen outlet for this pent-up energy and ill feeling (Dorling, 2010; Berardi, 2015; Power, 2022). Similarly, DeKeseredy and Schwartz (2005) theorise how economic integration may contribute to VAWG, as it may prompt some men to reassert traditional patriarchal roles in response to perceived threats to their dominance. At this point of bringing forth the idea of visceral habitus, it is timely to return to Beck’s idea of ‘risk’, of which contemporary examples include the Covid-19 pandemic and the COLC, to make sense of how violence against women and girls is increasing.

It can be argued that there are two levels through which one can understand the COLC. The first, is at a surface level and arguably an objective standpoint. Indeed, the cost of living has increased. This can be observed in the ever-increasing cost of the weekly food shop, alongside rising fuel, energy and utility costs which can be attributed to geopolitical events including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, which has led to a disruption of global supply chains, thus increasing the costs for imports, and the production of essential goods. These accounts are clearly pin-pointed by the British Government as constituting the causes for the rising cost of living in Britain (See Francis-Devine et al., 2024). The second layer of understanding the COLC is as a systematic process, caused by the entrenchment of neoliberal politics, austerity, and wider anti-statist ideology. It is argued by Dorling (2010) that the system of neoliberal capitalism is designed to produce and reproduce inequalities, across communities and households, which manifests in the form of a ‘society of enemies’ (Hall and Winlow, 2014) and ‘neoliberal patriarchy’ (Yardley and Richards, 2023). Thus, we contend that rising levels of violence against women and girls can, at least in part and at the broadest level, be viewed as symptomatic of the present social and economic situation.

Whilst the surface level reasonings for the COLC are not to be dismissed, particularly as geopolitical insecurity and wider global restructuring has led to the rise of economic insecurity and heightened competition in the labour markets, it is further argued that the very nature of the system itself needs to be examined. This is to map the complexities of the COLC, but also to recognise that the system of neoliberal capitalism has engineered social and economic life, to sustain and manufacture inequalities and harm, to allow the system to sustain and reproduce itself.

Rising rates of VAWG, largely at the hands of men can be linked to COLC, plays a significant role as a layer of risk in a risk society. This is not to position the COLC as the sole contributor to this rise of violence, but to recognise that violence at the interpersonal levels is sustained and reproduced through objective, symbolic and systemic modes of violence (Žižek, 2008) that exist in everyday life. This poisonous mix of a rising cost of living and austerity politics has arguably led to a rise of men who feel increasingly marginalised and powerless. The enaction of what could be termed ‘residual power’ can be seen at the domestic and interpersonal levels and is arguably fuelled by the intensification of economic alienation, exemplified by the relentless struggle against the COLC. Here, the notion of ontological insecurity can be refined and understood more precisely as ‘objectless anxiety’, and foregrounded against the backdrop of the deaptative socialisation of young men and the cultural reproduction of the socially and economically redundant visceral habitus (Hall, 2012).

Whilst highlighting the importance of broader social and economic factors in contextualising and contributing to the rising tide of violence against women and girls. Of course, as we briefly mentioned above, some violent men are relatively successful, therefore it is also important that this macro socioeconomic context is considered alongside the meso- and micro-levels in which we find the differentiation to be discussed in forthcoming publications. We cannot truly understand the key determinants of this violence and develop meaningful strategies to address the issue by exploring each level in isolation. It is imperative that as social scientists, we seek to develop a robust understanding of VAWG in all its complexity so that we can understand the level of intervention required to meaningfully address the problem and reverse the tide of violence we are witnessing with growing frequency against women and girls. Only when we adopt such a robust approach to understanding the issue will we have the capacity to truly address it.

References

Atkinson, R., and Jacobs, K. (2020) What Do We Know and What Should We Do About Housing? London: Sage Publications.

Beck, U. (1992) Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage Publications.

Berardi, F. (2015) Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide. London: Verso.

DeKeseredy, W. S., and Schwartz, M. D. (2005) ‘Masculinities and interpersonal violence.’ In Kimmel, M. S., Hearn, J., and Connell, R. W. (Eds.) Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities. California: Sage Publications.

Dorling, D. (2010) Injustice: Why social inequality still persists. Policy Press.

Ellis, A. (2015) Men, masculinities and violence: An ethnographic study. Routledge.

Francis-Devine, B., Malik, X., and Roberts, N. (2024) ‘Food poverty: Households, food banks and free school meals.’ House of Commons Library Research Briefing. [online]. Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9209/CBP-9209.pdf. (Accessed on: 19/03/2025).

Gibbs, N., Salinas, M., and Turnock, L. (2022) ‘Post-industrial masculinities and gym culture: Graft, craft, and fraternity.’ The British Journal of Sociology. 73. Pp. 220-36.

Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity. New York: Polity Press.

Hall, S. (1997) ‘Visceral Cultures and Criminal Practices’, Theoretical Criminology, 1(4): 453-478.

Hall, S. (2012) Theorizing Crime & Deviance: A New Perspective. London: Sage Publications.

Hall, S., and Winlow, S. (2014) ‘The English riots of 2011: Misreading the signs on the road to the society of enemies.’ In Pritchard, D., and Pakes, F. (Eds). Riots, Unrest, and Protest on the Global Stage. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hall, S., Winlow, S., and Ancrum, C. (2005) ‘Radgies, ganstas, and mugs: Imaginary criminal identities in the twilight of the pseudo-pacification process.’ Social Justice. 32. Pp. 100-12.

Kotzé, J. (2020) ‘The commodification of abstinence.’ In Hall, S., Kuldova, T., and Horsley, M. (Eds). Crime, Harm, and Consumerism. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kotzé, J. (2024) ‘On special liberty and the motivation to harm.’ The British Journal of Criminology. 65(2). Pp. 314-27.

Lynes, A., Yardley, E. and Danos, L. (2021) Making sense of homicide: A student textbook. Waterside Press.

Lloyd, A. (2018) Harms of Work: An Ultra-Realist Account of the Service Economy. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Power, N. (2022) What Do Men Want?: Masculinity and its Discontents. Penguin.

Rodríguez, S.G. (2012) The Femicide Machine. MIT Press.

Sanz, V. (2017) ‘No way out of the binary: A critical history of the scientific production of sex.’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 43. Pp. 1-27.

Valencia, S. (2018) Gore Capitalism. MIT Press.

Valencia, S. (2019) Necropolitics, postmortem/transmortem politics, and transfeminisms in the sexual economies of death. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 6(2), Pp.180-193.

Yardley, E. (2020) ‘Technology-facilitated domestic abuse in political economy: A new theoretical framework.’ Violence Against Women. 27(10). Pp. 1479-98.

Yardley, E., and Richards, L. (2023) ‘The elephant in the room: Toward an integrated, feminist analysis of mass murder.’ Violence Against Women. 29(3-4). Pp. 752-72.

Žižek, S. (2002) For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor. London: Verso.

Žižek, S. (2008) Violence: Six Sideways Reflections. London: Profile Books.

Žižek, S. (2016) Against the Double Blackmail: Refugees, Terror and Other Troubles with the Neighbours. Penguin.