What if the freedom we feel when using digital platforms is just a beautifully packaged illusion? We spend hours on TikTok, Instagram, OnlyFans, Tinder, BeReal, Snapchat, or Reddit, convinced that we are choosing, enjoying, and even liberating ourselves. But who really benefits? Spoiler: it’s not us. As ultra-realist criminologists argues, not everything that looks like empowerment truly is (Hall and Winlow, 2015). Digital leisure, once imagined as a liberating space, has become a structural machine of emotional, symbolic and economic exploitation (Raymen and Smith, 2020). And the most insidious part? It happens with our apparent consent. Or so we think.

We live inside an emotional economy where algorithms don’t reward what is valuable but what is viral. Not what is ethical but what is profitable. The logic is simple: the more you expose yourself, the more you’re rewarded. TikTok’s ‘For You’ page doesn’t promote creativity; it promotes emotional intensity. Tears, nudity, self-harm, humiliation, anything goes if it attracts clicks. This mirrors the principles of late-neoliberal capitalism, where an individual’s value is tied to market performance (Streeck, 2016). Psychologically, this virality of disturbing content also taps into our evolutionary and affective sensitivities, what Rozin and Royzman (2001) call negativity bias, where the brain is wired to pay closer attention to potential threats, pain, and spectacle.

In 2024, Ofcom reported that 57% of children aged 7-17 in the UK use TikTok daily, often with minimal parental oversight (Ofcom, 2024). Meanwhile, The Guardian (2022) reported that TikTok’s algorithms internationally and repeatedly pushed the ‘Blackout Challenge’ videos to children, resulting in tragic deaths later linked to the challenge. And it doesn’t stop there. One disturbing manifestation of this emotional economy is the practice of ‘sharenting’, whereby family vloggers monetise their children’s lives. YouTube and TikTok are flooded with ‘day-in-the-life’ content, birthday reveals and emotional breakdowns, produced and consumed like reality TV but starring minors. A stark example is the case of teen ‘kidfluencer’ Piper Rockelle, whose mother and partner now face lawsuits alleging exploitation and abuse, claims unpacked in Netflix’s documentary Bad Influence: The Dark Side of Kidfluencing. What does informed consent mean for a child raised as content? As Strohmaier et al. (2020) warn, this practice and the wider platform economy reward emotional over-exposure with visibility and symbolic capital.

But let’s be clear: this isn’t just about influencers or irresponsible parenting. This is a structural issue. And it’s working exactly as designed. Ultra-realist criminology dismantles the comforting myths of agency in late capitalism. What often feels like freedom is, in fact, a simulated agency, a carefully engineered illusion of choice that operates strictly within the limits of what the system considers profitable, acceptable, and self-defeating (Hall and Winlow, 2015). You are free to choose, but only from the options that will keep the machine running. This becomes especially clear when we look at platforms like OnlyFans. You can decide what to post, when to post, and how to brand yourself. But when your rent is due, your benefits have been slashed, and mainstream employment excludes or devalues you (Lloyd, 2018), how meaningful is that ‘choice’? This isn’t about traditional notions of deviance or criminality. We are not talking about ‘others’; we are talking about ourselves. Ordinary people are trapped in a structure that demands constant self-curation and emotional performance just to stay visible, relevant, or afloat.

Deviant leisure may sound like academic jargon, but its reality is raw and disturbingly familiar. It names those practices that seem transgressive (sexting, filtered selfies, livestreamed self-harm, ironic misogyny and performative outrage) but are, in fact, deeply integrated into the digital economy. They look like rebellion but in reality they are often rehearsals for visibility, monetised through clicks, shares and algorithms. Cultural theory once romanticised these acts as symbolic resistance, subversive gestures against social norms – but in actuality they are a form of hyper-conformity, rather than non-conformity (Kotzé, 2020). But ultra-realist criminology cuts through that illusion. These aren’t ruptures in the system; they are expressions of it, performances for power, not against it. Each one feeds a platform economy that thrives on our suffering, our vulnerability and our compulsion to be seen (Smith and Raymen, 2016). In the digital coliseum, an algorithmically built arena where pain is polished and applause is measured in interaction metrics, the user becomes both audience and gladiator: performing for survival, competing for visibility, and always one swipe away from erasure.

We live in an age where suffering is curated. It’s not just about what we feel, but how we present it. Anguish must be aesthetic. Anxiety must be shareable. Despair must be productive. From viral ‘breakdown’ confessionals to trends romanticising trauma, the performance of harm becomes a pathway to recognition. The issue isn’t that people speak about their pain (expression matters), but expression within a system that demands emotional exposure for engagement is not the same as autonomy. You can suffer – but only if your suffering is algorithmically legible and profitable. And if you don’t perform it, someone else will. Because in the visibility economy, not being seen means not existing. But being seen requires packaging yourself as a spectacle. And what once might have been intimate, collective or therapeutic now becomes just another product in the endless scroll.

As Debord (1967) warned, the spectacle doesn’t reflect reality; it replaces it. In that replacement, even our most personal forms of distress become raw material for platforms that extract affect like a resource, just another currency in the attention economy. There’s nothing rebellious in this. No rupture. No liberation. Just a perfectly designed loop of pseudo-transgression and aestheticised harm, repeated not out of resistance but out of ontological hunger – a desperate search for meaning, status or survival within systems that thrive on our fragility (Kotzé, 2020). But this loop doesn’t exist in isolation, it demands spectators. The digital coliseum relies not just on those who perform, but those who consume. As products of consumer culture, we are conditioned to take interest in the suffering of others, not with empathy, but with fascination. Kelly (2023) shows how 21st century media cultivates an obscene enjoyment, a compulsive pleasure in pain among audiences who repeatedly consume scandal, hate, and humiliation. Viewers are not mere witnesses but active participants deriving ecstatic thrill from exposure to transgression, yet Kelly argues it is the spectators who are truly ‘caught on tape’.

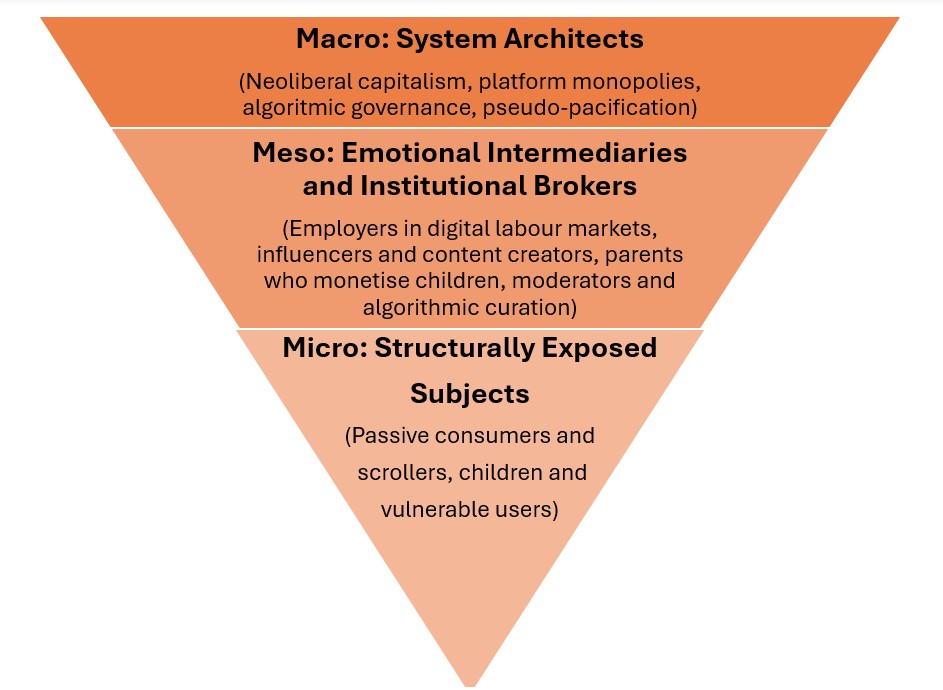

On OnlyFans, many marginalised women monetise their intimacy, which some call sexual empowerment. But how much empowerment exists within a structure that rewards exposure and punishes silence? Illouz (2007) and Han (2014) describe this as affective capitalism: a system where our emotions are valuable only when they can be turned into data. Yet, as Medley (2019) argues, even feminist pornography, which is often celebrated as resistance, succumbs to the same capitalist logic. What appears as empowerment is often an example of ‘hedonic realism’, the inability to imagine leisure or pleasure beyond consumer capitalism. Within this logic, consent is shaped not by autonomy but by economic desperation. Rather than resisting the mainstream, these practices are ‘precorporated’ (Fisher, 2009; Medley, 2019), already formatted to fit capitalist structures before they even begin. Claims to political agency may amount to little more than ‘hypercorporation’, the performance of resistance that deliberately reproduces the very dynamics it claims to challenge. So, are we really free if all we get to choose is how we market ourselves? To make sense of how power, visibility and harm are distributed in the digital ecosystem, I found it useful to represent these dynamics as a conceptual pyramid.

Figure 1. The Structural Logic of Digital Harm (Mayra Barrera: 2025)

This framework doesn’t just map behaviours – it reveals a structural order. Digital leisure isn’t free-floating; it’s stratified and each analytical layer performs a specific role in sustaining the system’s logic. As we move from macro-level structures to micro-level subjectivities, we see how harm becomes routine, not by accident but by design.

- Macro. System Architects. At the widest layer of the inverted triangle sit the system architects, the technological monopolies, platform owners, and algorithmic designers who define the digital environment. Through the political economy and surveillance infrastructures, they engineer desire, structure emotional expression, and embed neoliberal logic. The socio-economic system promotes competition and non-physical aggression, which creates the anxious, pseudo-pacified subjects visible in the other levels (Hall, 2012).

- Meso. Emotional Intermediaries and Institutional Brokers. The middle layer contains the intermediaries who translate macro logics into everyday practices. Influencers, content creators, and parents who monetise emotional labour function here as brokers of affect. Their actions exemplify what Hall, Winlow, and Ancrum (2008) termed special liberty: a narcissistic sense of entitlement to transgress ethical or legal boundaries with impunity. In digital capitalism, their behaviour is not a failure of moderation, but a predictable outcome. Alongside them are digital employers and moderators who enforce platform norms. These actors operationalise harm by converting emotion, intimacy, and identity into marketable content, all while appearing authentic or empowering. They don’t create the rules, but they enforce and benefit from them.

- Micro. Structurally Exposed Individuals. At the tip of the triangle, the narrowest but most densely populated, are the individual users, especially the structurally exposed. Children, racialised communities, neurodivergent users, and those with limited digital literacy face the highest vulnerability with the least power. Yet, their visibility is actively engineered; they are both product and audience. The vast majority of users are ‘passive’. They consume, like, share, and scroll, not always maliciously but often uncritically. Even when they reject certain content, their engagement sustains its visibility. Participation becomes complicity and disengagement threatens symbolic erasure.

Hovering over every level is a force less visible but more powerful than any single actor: the ideological and algorithmic logic of late neoliberal capitalism. This is not just a technological infrastructure, but an ideological architecture. It scripts desire, visibility, and value, encoding neoliberal principles into reward systems, including what to feel, when to share, and how to perform pain. The system doesn’t need to force you, it only needs to train you. And that’s the paradox, we are not outside the pyramid. We’re inside it, producing, consuming, and reproducing the very logic that exploits us.

Governments legislate. But they move slowly, clumsily. France, Germany, the UK and the EU all have attempted content regulation but without dismantling the architecture of harm. Such legislation addresses the symptoms, not the system, targeting the visible effects while leaving the structural logic untouched. Deleting violent videos isn’t enough if the algorithm that promotes them remains untouched. We need an ethical approach that sees harm not just as a legal issue, but as a structural feature of digital capitalism. Because this isn’t just about content, it’s about how lives, emotions and identities are structured for profit. It’s anxiety, burnout, compulsive exposure, and the slow erosion of autonomy sold back to us as empowerment.

Digital leisure, far from offering refuge, becomes a form of pacified compliance. What appears as transgression – sexual display, emotional oversharing and commodified vulnerability – is, in fact, a desperate negotiation with invisibility. These performances don’t subvert the system, they sustain it, one post, one click, one trauma at a time. As Hall and Winlow (2015) argue, capitalism no longer dominates through force when it can seduce us into exploiting ourselves. We internalise market logic so deeply that we brand our pain, aestheticise our despairs, all while believing we’re empowered. The system creates the suffering whilst providing a commodified coping strategy that it also profits from. This is what ultra-realism calls ontological insecurity: a pervasive sense of meaninglessness, of being structurally out of place, that drives us to seek validation in commodified forms (Raymen and Smith, 2020). But in the attention economy, visibility is conditional. Social media becomes the mirror where we hope to ‘matter’ (Billingham and Irwin-Rogers, 2022), even if it means performing harm, overexposure or reducing ourselves to spectacles. Recognition comes at the cost of your intimacy, stability, and self. This cycle is reinforced by what Hall et al. (2008) termed ‘pseudo-pacification’: a form of control that doesn’t rely on punishment and subjective violence, but on pleasure, distraction, symbolic gratification, competition, and structural harm.

Digital leisure is no longer just entertainment; it’s a battlefield — symbolic, emotional, and political, where bodies, attention, and identity are negotiated and commodified. What used to be play is now performance. What once offered freedom now extracts value. And where are we headed? If we do nothing, the future won’t be dystopian, it will be a more optimised version of today. Algorithms won’t protect us, they’ll predict us. Content won’t be more human, it will be more addictive, manipulative and profitable. Surveillance will become ambient. Consent will become decorative. The line between intimacy and exposure will vanish. As Zuboff (2019) argues in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, surveillance infrastructures are not passive observers, but systems actively shaping behaviour to align with corporate goals. Similarly, Kuldova (2020) shows how algorithmic governance turns human interaction into predictable, governable, and monetisable flows of data. Within this logic, other content creators are not just peers but competitors, obstacles to recognition, visibility, and symbolic survival. In various online communities, users employ the very architecture of the system designed to protect users (e.g. reporting posts) as weapons through which they can attack and undermine the competition, potentially causing harm. Here, symbolic violence can result in a kind of symbolic death for the victim, via the erasure of visibility within the digital economy.

Technology is not the enemy. Technological advancement is necessary, laudable, and even emancipatory when developed with justice, care and democratic intent. The problem isn’t platforms or AI themselves, but how they’re designed, owned and weaponised within systems that turn attention into capital and vulnerability into spectacle. The real issue is structural. Algorithms don’t exploit people. Systems do. Systems that engineer desire, monetise emotion and normalise harm while branding it as freedom. As McGowan (2016) argues, capitalism doesn’t suppress desire, it feeds on it, manipulating our longing by promising fulfilment through consumption while ensuring that fulfilment remains perpetually deferred. These systems tap into the very structure of human subjectivity, turning lack into a profit model. It’s not just a question of values, it’s about how our desires, technologies and lives are being structured. Changing that requires not only ethics, but also politics, collective imagination and structural conflict.

The threat isn’t AI, it’s symbolic capitalism, a system where every difference becomes a product, every connection becomes data and every wound becomes content. This is not a technical crisis. It’s a cultural, emotional and existential one. The question is no longer whether we can resist; the real question is whether we are willing to imagine and build other ways of living, connecting, showing up and caring. Ways that honour dignity, not market visibility. Because if we don’t, we will continue to celebrate our slavery as if it were autonomy. And the coliseum, though digital, will keep devouring bodies. Only now, not with roars or spectacles but with filters, likes and monetisation.

We can’t afford to be spectators anymore. It’s time to leave the coliseum.

References

Billingham, L., and Irwin-Rogers, K. (2022) Against Youth Violence: A Social Harm Perspective. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Debord, G. (1967) The Society of the Spectacle. Paris: Buchet-Chastel.

Fisher, M. (2009) Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Winchester: Zero Books.

Guardian. (2022). ‘TikTok served blackout challenge videos to children minutes after joining’. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/nov/02/tiktok-served-blackout-challenge-videos-to-children-minutes-after-joining. (Accessed on: 17th June 2025).

Hall, S. (2012) Theorizing Crime and Deviance: A New Perspective. London: Sage Publications.

Hall, S. and Winlow, S. (2015) Revitalizing Criminological Theory: Towards a New Ultra-Realism. London: Routledge.

Hall, S., Winlow, S. and Ancrum, C. (2008) Criminal Identities and Consumer Culture: Crime, Exclusion and the New Culture of Narcissism. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Han, B.-C. (2014) Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power. London: Verso.

Illouz, E. (2007) Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kelly, C. R. (2023) Caught on Tape: White Masculinity and Obscene Enjoyment. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kotzé, J. (2020) ‘The commodification of abstinence.’ In Hall, S., Kuldova, T., and Horsley, M. (Eds.) Crime, Harm, and Consumerism. London: Routledge.

Kuldova, T. (2020) ‘Algorithmic governance and the opacity of power’. Big Data & Society. 7(2). Pp.1–5.

Lloyd, A. (2018) The Harms of Work: An Ultra-Realist Account of the Service Economy. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

McGowan, T. (2016) Capitalism and Desire: The Psychic Cost of Free Markets. New York: Columbia University Press.

Medley, C. (2019) ‘The business of resistance: Feminist pornography and the limits of leisure industries as sites of political resistance.’ In Raymen, T., and Smith, O. (Eds.) Deviant Leisure: Criminological Perspectives on Leisure and Harm. London: Palgrave.

Ofcom. (2024) ‘Children and parents: Media use and attitudes report 2024’. [online] Available at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/265961/children-and-parents-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2024.pdf. (Accessed on 17th June 2025).

Raymen, T. and Smith, O. (2020) Deviant Leisure: Criminological Perspectives on Leisure and Harm. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rozin, P., and Royzman, E. D. (2001) ‘Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion.’ Personality and Social Psychology Review. 5(4). Pp. 296-320.

Smith, O. and Raymen, T. (2016) ‘Deviant leisure: A criminological perspective’. Theoretical Criminology. 20(2). Pp.196–212.

Streeck, W. G. (2016) How Will Capitalism End? London: Verso.

Strohmaier, H., Murphy, C., DeRiggi, S., and Brunner, R. (2020) ‘Sharenting: Children’s rights and digital media’. Journal of Family Studies. 26(1). Pp.78–92.

Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile Books.